This post covers another one of Bloomingdale’s lost structures. It was written by Pam Tice, a member of the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group’s Planning Committee.

When you walk from West 96th to 91st Streets on Columbus Avenue, or walk east from Broadway to Columbus on those streets, you’ll notice you are on a hill. The crest of the hill on 91st Street, about 100 feet west of Columbus, is the location where, starting in 1764, a colonial mansion stood for 130 years. Originally, it was surrounded by a 300-acre estate. Over the years, though, the land was whittled back through legacy gifts and real estate sales, as the development of the West Side played out until finally, just the mansion stood, surrounded by a small park. This structure and the land encapsulates the history of our Bloomingdale neighborhood, and is presented here.

In 1764, wealthy merchant Charles Ward Apthorp built what was widely recognized as one of the finest mansions in all of New York City. Like many of his contemporaries, Apthorp purchased land on the west side of Manhattan, no doubt picturing himself as one of the landed gentry of the American colony. He had moved to New York from Boston where his father, Charles Apthorp, was one of New England’s wealthiest merchants, and served as the paymaster and agent for the Royal Army and Navy, furnishing supplies and money to the British forces in Boston and Nova Scotia. He also imported and sold many kinds of goods, including slaves. His eighteen children married into many of the other prominent families of the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Now in New York, Charles Ward Apthorp married Mary McEvers at Trinity Church in 1755. She was the daughter of John McEvers of Dublin, another successful New York merchant. They had ten children: Charles, James, George, Grizzel (named for her Boston grandmother), Eliza, Susan, Rebecca, Ann, Mary/Maria, and Charlotte; six of them lived to adulthood.

In 1762 and 1763, Charles Ward Apthorp purchased nearly 300 acres in Bloomingdale from two owners, Dennis Hicks and Oliver de Lancey, whose ownership can be traced back to Dutch landowners, starting with Bedlow. I. N. Phelps Stokes, in his book The Iconography of Manhattan, details the purchases of the Apthorp Farm which was also known as Elmwood, recognizing the beautiful trees surrounding the mansion. The house was finished in the early summer of 1764, located on a hill overlooking the Hudson River.

A short drive from the home led to the Bloomingdale Road, then the westside’s main thoroughfare. The estate also included two lanes that served as shortcuts to neighboring estates, including Apthorp Lane that stretched all the way east through the land we know as Central Park to the Boston Post Road near today’s Fifth Avenue.

The estate was described in a later advertisement:

300 acres of choice rich land, chiefly meadow, …on which there are two very fine orchards of the best fruit …an exceeding good house, elegantly furnished, commanding beautiful prospects of the East and North-Rivers, on the latter of which the estate is bounded. Also, a two-story brick house for an overseer and servants, a wash house, cyder (sic) house and mill, corn crib, a pidgeon (sic) house, well stocked, a very large barn, and hovels for cattle, large stables and coach houses, and every other convenience. About the dwelling house is a very handsome pleasure garden, in the English taste, with good kitchen gardens well furnished with excellent fruit trees of most kinds.

Here is a sketch view of Elmwood:

Charles Ward Apthorp was one of the prominent Royalists of New York City, serving on the Royal Governor’s Council 1763-1783, through the turbulent years of the American Revolution. After the Revolution, he was charged and convicted of treason, but for reasons not documented, he was permitted to keep his estate, but lost his holdings in Massachusetts and other New England states.

One account of Apthorp describes his flight to the Royal Governor’s ship in June, 1776, when he was summoned before the provincial Congress as a suspected Loyalist. In 1779 he was indicted for treason and the following year his Bloomingdale estate was offered for sale. Nevertheless, he was allowed to return to New York and acquitted of the charges against him.

The Apthorp home in Bloomingdale played a role in the 1776 Battle of Harlem Heights. As the British troops moved into Manhattan, the American Patriots moved up the island to the Bloomingdale neighborhood. Under the authorization of the Provincial Council, General Washington took over the mansion as his headquarters before moving uptown to Colonel Roger Morris’ mansion, today called the Morris Jumel mansion. On the evening of September 14, 1776, in the Apthorp drawing room, Washington and his men planned the operation that would send Nathan Hale to spy on the British on Long Island—which then cost him his life.

After the American patriots were pushed further north, the Apthorp home became the headquarters, at various times, of the British Generals Cornwallis, Clinton and Carlton for the duration of the British occupancy of the city, until 1783.

On January 3, 1789, Maria Apthorp’s wedding to Hugh Williamson took place at Elmwood. The family’s connection to the new United States appears to have been fully realized, as she married a delegate from North Carolina to the Congress which was meeting in New York City at that time. Williamson was 58 years old, compared to her 22 years—perhaps prompting James Madison’s remark to a friend that he hoped that this beautiful girl was “pleased with her bargain” and hoped she would “never repent.” Maria died in the early 1790s, after having two sons, both dying as young men.

Hugh Williamson was both a doctor and a statesman. Older than all of the Apthorp children, he took charge of consolidating their Bloomingdale land under his name, and then paid-off a mortgage on the property. He never remarried, and when he died in 1819, he left the property to his niece Maria, daughter of Charlotte Apthorp, and the wife of Alexander Hamilton’s son.

Charlotte Augusta Apthorp married John Cornelius van den Heuvel, and they built their mansion on a portion of land south of Elmwood. Their mansion later became Burnham’s Hotel (1833) and eventually their land was the site of the Apthorp Apartment House, built in 1908. Their granddaughter married John Jacob Astor III, thus bringing the Astor family name onto certain property deeds in the neighborhood; the Astor son, William, built the Apthorp.

Yet another Apthorp daughter, Rebecca, appears on early Bloomingdale maps as the owner of some remaining woodland lots totaling 50 acres—her name appears on mid-19th century maps.

Charles Ward Apthorp died in 1797. In 1799, William Jauncey, a wealthy Englishman, purchased Elmwood and its remaining land. Apthorp Lane became Jauncey Lane. Accounts differ as to whether he was a married man with no children or a bachelor, but his niece, Mary Jane Jauncey (who may have been an adopted child), was destined to inherit his fortune. When she eloped with a Colonel Herman Thorne, her uncle was unhappy, but did not cut off her family. In Jauncey’s final will, he left the Elmwood estate to her son, William Jauncey Thorne, when he became 21 years old, and providing he changed his last name to Jauncey, dropping the Thorne name.

William Jauncey died in 1828; in 1829 the Thorne family moved to Elmwood. They did not stay long, however, and moved to Paris in 1830 where they lived in lavish style in the leased Hotel Martignon on the rue de Varenne. Their son, William, never made it to his 21st birthday when he would have inherited Elmwood. He died in England at age 19 when he was thrown from a horse while hare-hunting with his Cambridge friends. A second son died while serving in the Mexican-American War; a third son eloped to South America with an Italian opera singer. A daughter ran away with a Frenchman (she later returned home); another daughter ran away to South America to become an opera singer. Still another married a French baron, but had to sue her parents to receive a promised dowry. The Thornes returned to New York in 1846, and in 1849 built a large home at 8 West 16th Street. There is no record found as to how or if they used the Elmwood estate, but retreating to the Bloomingdale countryside was still, no doubt, a popular summer activity.

News accounts of Colonel Thorne covered his ”fortunate marriage” and began to refer to “Colonel Thorne’s Elm Park.” An article about wealthy New Yorkers interested in horse racing discussed the “Elm Park Pleasure Ground Association,” a membership organization that leased the grounds of Elmwood for their track. The newspaper account indicated that the group investigated “antecedents” as part of their membership approval. No person was given access to the track “in Ninetieth Street” unless they were a member, and goes on to report “… these gentlemen, although seen with the habitues of Bloomingdale, form a quite separate class.” When Colonel Thorne died in 1859 the fast horse-racing gentlemen were concerned about the loss of their track, and were investigating moving it to the new Central Park, an early example of New Yorkers finding their space in the new park. (No such racing track was designated.)

On May 4, 1860, The New York Times printed a sad short piece about the auction of “Elm Park” and the end of an era of rural country living in Manhattan. The next day, the Times reported that the “large property belonging to the Jauncey estate, and more recently to the estate of Colonel Thorne, located between Eighty-ninth and Ninety-third Streets and Sixth and Tenth Avenues, and comprising about 500 lots,” was sold at the Merchants Exchange by Anthony J. Bleeckee. There appear to have been various bidders on pieces of the property, although not by name.

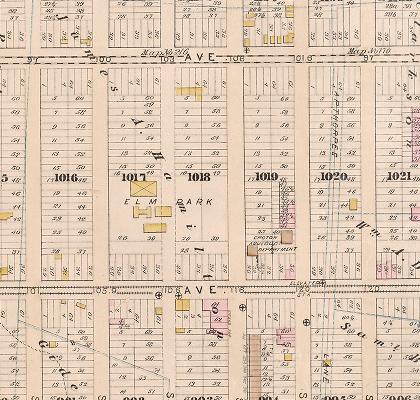

Nevertheless, some portion of the land and the old mansion house remained intact. Elm Park became a prominent feature of the Upper West Side neighborhood. In the 1860s it is referred to as “Conrad’s Elm Park.” In the 1860 federal census, a George Conrad, his wife and six children are listed as a household that the census taker labeled “Elm Park Pleasure Grounds and Elm Park Hotel.” The other people listed in the census are “three barkeepers, 3 domestics and 3 laborers.” All are German immigrants. This map of the mid-1860s shows the park’s dimensions and structures within.

In the Civil War years, Elm Park was referred to in news accounts as the place used by various New York regiments to gather as hundreds of soldiers prepared to head to the South to fight. Much of the city’s open space was used in this way—Jones’ Wood on the eastside, and numerous sites further downtown. These encampments in Elm Park at various times included the Lincoln Calvary, the New York Mounted Riflemen, and New York’s 29th Regiment, an all-German military unit under Col. A. von Steinwehr.

After the war, Elm Park continued to be used as a picnic ground usually following a military parade. The growing influence of German immigrants offering summer outdoor entertainments with music, dancing and beer-drinking in many places in the city included Elm Park. The Saengerbund, a confederation of German Glee Clubs, met in the city, and had picnics at Elm Park. A group gathered in the Park to watch a balloonist take off—a Frenchman who performed from a trapeze while he sailed out over the Hudson and landed in the water (he was rescued). The Spiritualist Society gathered there and generated numerous news reports, some making fun of this popular post-War activity of calling up the spirits of the departed.

Other accounts of the Apthorp Mansion indicate that it became a saloon and dance hall. Further, its abundant outdoor space could accommodate many thousands of people at summer events. When the mansion was serving as a hotel, it was said to have a large outdoor platform for dancing at park events. Finally, when the property was sold in 1894 (after the mansion was removed) the owners/heirs were the Bernheimer family, although it was not clear how long they had been the owners. This is the same family that were owners of the Lion Brewery further uptown at Columbus Avenue and 108th Street. There is evidence of Bernheimer ownership of other lots of land close to Elm Park, as noted in real estate transactions reported in the newspapers.

On July 12, 1870, an event occurred at Elm Park that once again put this space at the heart of the city’s history. Several organizations of Protestant Irish Americans that together were part of the Loyal Order of the Orange marched uptown that day to a celebration and picnic at Elm Park. July 12 commemorated the date of the victory of the Battle of the Boyne of William III, the King of England and Prince of Orange, over James II in 1690. Just as we see this phenomenon of “race ascendancy” today, the Orangemen of New York City were in league with the nativist Anglo-Americans who were reacting to increasing immigration of Irish Catholics.

As they marched, the Orangemen passed work crews of Irish laborers laying pipe at 59th Street, and, further along, working on broadening the Boulevard (later named Broadway). They taunted the workers with slurs. The Irishmen gathered, armed with clubs, and followed the marching Protestants, and, when they reached the Park, a riot ensued. Some blamed the New York City Police Department who “withdrew” as they decided their duty had ended when the parade reached the Park. Eight people were killed on this day, and many more wounded.

This 1870 riot sparked an even larger riot in 1871, although not on the West Side. That year, the Tammany government first denied a permit for 1871, keeping their Irish constituents happy, but then succumbed to pressure from the city’s elites and issued the permit. Historians of the city view this event as one of the key moments that loosened Tammany’s hold on the city government, as the city’s elites had “allowed” Tammany so long as the leaders could keep the immigrants under control. It took more time, but eventually Tammany was broken and a movement arose to take over city government by the ”wisest and best.”

The earlier riot in 1870 appears to have had no effect on the continuing operation of Elm Park. News accounts of the events that took place there began to refer to “Wendel’s Elm Park.” Louis Wendel had become the Park’s manager, and was linked to the management of other city spaces. If the Bernheimers owned the Elm Park space at this time, Wendel may have worked for them. By the 1880s, he had management over Elm Park, Lion Park (near the Lion Brewery), the Wendel Assembly Rooms on West 44th Street, Schutzen Park in Brooklyn, and the West Side Casino. When Elm Park was finally sold in the 1890s, a news story mentioned a brewery there, although there is no photo, map, or other reference to determine the existence of that facility.

Wendel was a New York character representing a time in the City’s history when Tammany still ruled. He became an Alderman in 1884 and was caught up in the “Broadway Railroad Steal” when nearly all the City’s Aldermen were said to have taken major bribes for the extension of the surface streetcar service south from Union Square. In a State Senate investigation in 1886, the Aldermen came to be known as “the Boodle Aldermen.” Eventually, some were brought to trial and convicted, but not all of them, and Wendel escaped this fate.

Long after Elm Park had closed down, in 1907 Wendel was investigated, court martialed, and removed from his position as Captain of a New York Guard unit, the First Battery, based at the armory on West 44th Street next to his “Assembly Rooms.” Wendel was removed for stealing funds. He died in 1914, reported to be ”a broken man” living on a small allowance supplied by his wife.

In 1891, the Apthorp mansion was torn down. It was important enough in the City’s history that The New York Times wrote an “obituary” for the house, describing its history.

The Apthorp and Jauncey estates continued to create property problems in the Bloomingdale neighborhood until 1911 when a settlement was made and described in The New York Times. The little lanes crossing the Apthorp estate, as well as the Bloomingdale Road, running north/south between Amsterdam and the newly-named Broadway became parcels of land to which the heirs to the estates claimed ownership, initiating lawsuits to hold on to their parcels. Some say that these “paper roads” held up development in this West Side neighborhood until all cases were finally cleared.

Here are two photographs of the mansion just before it was demolished in 1891:

Bloomingdale’s Apthorp family lives on in New York City history in just a few places. Trinity Church has a family vault where Charles Ward Apthorp and other family members are interred. There is an Apthorp chair at the Metropolitan Museum, in their American collection, although it may be from the Boston branch. And, amazingly, the New York Botanical Garden has included the Apthorp Mansion in their depictions of important New York City buildings in their holiday train display.

Sources

Stokes, I.N. Phelps The Iconography of Manhattan Island 1498-1909 Volume 6. New York: Robert H. Dodd, 1915-1928

The New York Times archive

Columbia University’s Real Estate Record

New York Public Library’s Digital Collections – maps

Museum of the City of New York’s photo collection

Daytonian blog posts

Library of Congress Chronicling America collection of New York City newspapers

McKenney, Janice E. Women of The Constitution: Wives of the Signers (online at Google Books).

Is the Apthorp at 79th and Bway named after the family?

Yes!!

Pingback: How 10 Famous NYC Buildings Got Their Names | Untapped Cities

Pam, great article. Thank you!